- Home

- John Glynn

Out East Page 2

Out East Read online

Page 2

“Is that a BC bud?” he asked, nodding to Fred. “I don’t recognize him!”

“Oh, him?” I said, heart stammering in an unfamiliar way. “He’s no one.”

Chapter Two

Shortly after Christmas, Kicki died. She was my last living grandparent, my mom’s mom. She’d outlived my grandfather by a year. She died in her own bed, in the in-law apartment above my aunt Ellen’s house, just down the street from my parents.

In her final hours we surrounded her, clutching Styrofoam cups of Dunkin’ Donuts coffee. Kicki was our matriarch. My cousins and I worshipped her.

I went back to Massachusetts for the funeral, but in my grief left my suit bag on the train. It had contained my jacket, dress pants, shirt, tie, and belt. My dad raced me up to the Jos. A. Bank before it closed. Then he called Vladimir’s Tailors and convinced them to open early the next day, a Saturday, to hem the pants first thing.

I hated myself for losing the suit bag, and my dad’s instinct to kindness only accentuated my sense of ineptitude, my inability to be an adult. He was a good man and a problem solver. I felt like a hot mess.

The next day I was ablaze with insecurity. I felt awkward in the new suit and worried it was too large and boxy. I tended to avoid wearing formal clothes in general because they made me feel like an imposter, a kid playing dress-up. I processed down the aisle, the pages of my eulogy tucked in my pocket.

I took a seat in the pew next to my cousin Jay. He was a year younger than me. We’d gone to the same middle and high schools and were best buds. He was going to deliver a eulogy, too.

I remember standing at the lectern, hands trembling, staring out at the two hundred or so people who filled the church, but I have no memory of the speech itself. Instead I have an overmemory. I’m sitting in the pew, watching myself deliver the eulogy. I’m separate from the person in the pulpit. I am not that person. That is not who I am. I am the person in the last row, by the door.

There were sixteen of us, and we arrived in three waves. Five older cousins, eight in the middle, and three babies at the end.

I was the middle of the middle, a fall baby, born on the feast day of Saint Jude. When I was a kid my mom encouraged me to pray to him. He was the patron saint of hopeless cases, and I absorbed his iconography. Every year during the last week of October, Holy Name Church in Springfield held a weeklong novena in Saint Jude’s honor. My mother attended each night after dinner, sometimes with a sister or two, often with Kicki. One evening my mom brought me back a prayer card. On one side stood Saint Jude, haloed and barefoot in an emerald meadow. On the other, a Catholic prayer, which I read while kneeling. I tacked the card to my corkboard and asked Saint Jude to intercede when I needed it.

I held a liberal interpretation of hopeless cases and often prayed for frivolous things. A win for my basketball team. A Super Nintendo. An A on a science test I hadn’t studied for. But mostly, at night, I prayed for a sibling.

I was an only child, the only only child I knew. At five I wrote a story, dictated to my mom and illustrated by me in Magic Marker, called “The Wishing Turtle.” In it, the Wishing Turtle wishes for “another him.” One day, as the wishing turtle is basking by his lake, another him appears in the water. The two meet and are instantly inseparable. They play a game called “splash the knocky turtle” and are together forever. The end.

Even at five I was thinking about the mystic connection one could discover in another. The idea that you could travel through life with someone seemed to me like the zenith of happiness. Life, like a double-sticked Popsicle, was meant to be cracked down the middle. Here, I’d say. One half for you, one half for me. Red’s my favorite flavor, too. When you finish, keep the stick. There’s a joke written on it.

My mom had me when she was thirty-five. She got pregnant again at thirty-seven. In a beach photo she wears a loose nautical shirt, her body freckled and lithe save for the smallest melon forming beneath her hand. I’m in a diaper, holding on to her leg. There was a miscarriage. I don’t know if my parents tried again.

The eight cousins in the middle had been born in a three-year cluster, and of those eight, seven were boys. In the summers we were herded through life together. Each morning we swam at the town pool, competing for Red Cross cards and pieces of bubble gum wrapped with stick-on tattoos. My mom and aunts took turns making lunch. Eight PB&Js lined across the table. Eight small glasses of 2 percent milk.

On Fridays we had cousin sleepovers and watched Indiana Jones and Home Alone in my aunt Ellen’s attic. We ate pizza and washed it down with orange soda. At bedtime we rolled our sleeping bags across the attic floor and sang the theme song from Stone Protectors.

As the others drifted to sleep, I’d lie awake, breathing in the scents of my pillow from home. The windows were open and my ears were like conch shells, amplifying every noise: crickets and joggers, insects battering the screen. Then the baleful moan of a distant train, a sound that, for reasons I didn’t understand, made me miss my mom, my own bed, my stuffed animals and blanket. I snuggled next to my cousins, even in the heat, and tried to be brave.

I was in a pig pile, physically surrounded, yet somehow I felt dislocated. Different. I didn’t understand the loneliness. I just knew it was there. Like the moon gone dark.

The next morning there was a rush of light. My cousins yawned and stretched and cracked their ankles. The air had gone cooler, a dew clung to the screen. I felt a jolt of anticipation knowing my mom would pick me up in a few hours. Everything was better in the morning, even the leftover brownies, which Ellen let us eat off the pan with our cereal because she was the youngest, hippest aunt.

Kicki had come over that morning, too, and was sipping tea from a clear mug. She watched us eat and feigned concern.

“Oh my word. Brownies for breakfast. What will your mothers think?”

Our mothers shared the same maternal gaze. They were the Kelliher sisters—five of them, one in each grade, the loud laughers, the popular ones. They had all been champion synchronized swimmers. Good girls. Bad Catholics. They’d grown up with nothing, but had all they needed.

My mom was the fourth girl. Named Thomasina, Thom for short, because my grandfather’s name was Thomas, and my grandparents were certain they’d never have a son (they did two years later, my uncle Jim, whom everyone called Kell). Growing up she disliked her name, but she eventually learned to love it. In a town of Barbaras and Lindas, she was a Beyoncé. But I was given a short, plain, one-syllable name for a reason.

My mom met my dad while jogging in Forest Park. A game of tennis followed, along with a trip to Friendly’s for ice cream sundaes. In a scratched booth, over scoops of chocolate chip, my dad explained that he had just gotten into medical school in Italy. In six months he’d be moving to Perugia. He didn’t know the language and could barely afford a plane ticket. My mom was sold. Three days later, they were engaged.

My mom went to Casual Corner, a discount store at the Holyoke Mall. She found a white dress on the clearance rack and it became her wedding dress. She wore a wreath of flowers in her hair.

They spent one winter curled up on a kitchen floor in Perugia, sleeping as close as they could to the open oven, too poor to afford an apartment with heat. But they were young and beautiful and in love; the vagaries of the world faded to ether.

This was my foundational narrative. The master truth that shaped all the others. Love hits you instantly, effortlessly, and all at once. It never fades, it never changes, it endures forever, and it defines you. When you find that person, you push your chips all in.

You just know.

You just know.

You just know.

Thirty-five years later—my dad now a successful oncologist, my mom an elementary school teacher—they were still wildly in love. They’d come from nothing and built a life together. They had raised a child who wanted for nothing, gave him a small-town childhood, a house with a backyard, a driveway with a basketball hoop, a bicycle, a car. And now he lived in the city

, in Tribeca, where Robert De Niro and Jay-Z lived, and he worked for a publishing company, and went to concerts, and spotted famous people on the street. When his grandmother died, he delivered her eulogy.

They had been good parents. They deserved a happy son.

Chapter Three

On the Friday of MLK weekend we drove up to Stratton, Vermont. My friend Caroline’s parents had a condo by the mountain, and they let us use it often. There were seven of us heading up in three separate cars. I was in the late-departing car with my friend Billy.

Billy and I stopped at my parents’ house in Longmeadow, Massachusetts, so I could pick up my skis. My mom handed us a bag of Nestlé Crunches, Goldfish, and cans of soda. Our house, a white colonial with green shutters, sat on the corner of a busy street, but the neighborhood was glazed with the kind of silence that only accompanies heavy snowfall.

“Drive safely!” my mom implored through the window.

“Don’t worry, Thom! We’ll be safe,” said Billy.

“Tell Caroline and all the BC buds I say hi! And no driving after après. Love you both!”

We drove through Springfield and got off at exit 6 for Dunkin’ Donuts. I ordered a large iced coffee and Billy got a sausage biscuit. After Amherst, civilization started to peel away. We passed Hatfield, Whately, Greenfield, Northfield, towns seemingly built for darkness and solitude. The world of Ethan Frome and perpetual winter, towns tinted blue.

A Talking Heads song came on, the lyrics meshing with my coiled thoughts. How did I get here. My mind wandered back to our Christmas party and my conversation with Fred. He had told me he liked me. He had said that if I were gay, we could be together. I imagined what that would look like. Being together. Not just with Fred, but with anyone. When I thought about love I had to track back to high school, to an ethereal pole-vaulter, a girl named Jodi. During her track practice I’d watch as Jodi lofted to the sky, her legs pale and weightless, her mind unburdened, her bone-thin body knifing through the clouds. I’d gaze out from the tennis courts, halting my own practice to peer through the chain link. Jodi and I went to every school dance together. We were best friends but dated other people, lost our virginity to other people. When we finally hooked up senior year, it felt like a terminus. I’d expected the encounter to raze my life and rearrange it, to form a foundation upon which everything else would balance. Physically it was great, but no different from any other hookup. I pictured the pole-vaulting bar, the vault pit, the blue cushioned mat. We’d cleared the hurdle and landed safely on the other side. That was that. Back in line. Same as it ever was. Same as it ever was.

I’d never been in a long-term relationship, though I’d wanted one desperately. As my friends paired off I’d started to wonder why I wasn’t connecting. The answer was I had no idea, and the not knowing was what kept me up at night.

Billy and I got to the condo around 10:15. A crackling fire warmed the great room, drenching its vaulted walls in long shadows. Everyone was drinking big glasses of malbec.

“You made it!” Caroline cheered as we took off our Bean boots. “Bring your stuff upstairs, you guys are in the Animal Room with Shane.”

Shane often came to Vermont solo, without Mike. Mike wasn’t much of a skier, but Shane loved the outdoors. The rugged opulence of Vermont suited him.

The Animal Room had three adjoining bunk beds dressed in Ralph Lauren blankets. I changed into sweatpants and a Red Sox T-shirt and joined the others downstairs. Shane fed the fire with dry birch, the flames glinting off the moose antlers on the mantel.

“Who wants to smoke?” someone asked.

I donned my boots and went out to the deck. Shivering, huddling, no coats, we breathed in the weed until it cherried. Evan’s girlfriend, Lizzie, cupped the bowl from the wind. The cold air made it impossible to distinguish between the pot smoke and our frosty breath. I felt the high slipping down my arms, narcotizing every muscle.

“I feel like Jack from Titanic when he’s in the water,” I said.

“He could’ve gotten on that goddamn slab of wood,” said Evan. “Lizzie, you remind me of Rose. So high-maintenance.”

“Shut up, I am not!”

“Shane, you’re definitely Rose’s mom,” I joked. “And Caroline’s the Unsinkable Molly Brown.”

“Who are you?” Caroline asked me.

“I’d say I’m Jack because I’m definitely in steerage. But I can’t draw. So I’m probably the Italian sidekick. Or the guy who hits his head on the propeller.”

Between the red wine and the weed (I rarely smoked), I felt, as I stared into the fire, a deep, battering acceleration of time. I closed my eyes and I was five years old. I opened them and I was twenty-seven. I closed them again and I was forty. I opened them and I was seventy-eight. My life was hurtling by without me, and the intense compression ignited a sense of dread. I felt the sudden need to drink more aggressively.

“Let’s play Kings.”

It was a passive, slow-moving drinking game, perfect for a big group. We’d played it in college, usually as part of a pregame. Caroline found cards and fanned them in a circle. We went all the way through the deck.

The next morning Shane drove to the general store for bacon, eggs, and avocados. Caroline made a scramble. We drank mugs of strong coffee. By nine thirty we were in line for the chairlift.

We were all strong skiers, so we stuck to the black diamonds, which were less crowded. I dashed my edges into the snow, feeling the burn in my quads and hamstrings. The wind howled through my teeth, stabbed through the vent in my goggles, whipped my lift ticket against my jacket. We skied as a loose pack, stopping only when the trails converged. Skiing was, in the end, a solitary sport.

We pushed hard through the day and then it was après. At Grizzly’s bar I had four Long Trails, two Fireball shots, and the rest of Caroline’s Bloody Mary. I spotted a girl from high school I’d lifeguarded with sitting two tables away. Back then some kids had styled a March Madness–type bracket for girls in our high school. Everyone voted online for who they thought was the hottest. The girl at the table had been a one seed. I didn’t say hi.

Back at the house I consumed two bottles of red wine with dinner and smoked more weed on the deck. I played beer pong. I played Kings. I played Never Have I Ever. I played music and we danced around the living room. By the time we found a cab that would pick us up, I was nearly nonverbal.

I remember entering the Red Fox Inn, and I remember the bar. I remember thinking our city clothes made us stand out. I remember believing that, since Kicki’s death, nothing really mattered one way or the other. I remember a tequila shot. Two tequila shots. And many small bags of Doritos clothespinned and hanging from a string. You could buy them for a dollar. I must have eaten some.

The next thing I remember was the light murdering my eyes in the Animal Room. The smell of bacon. Caroline telling Evan to make coffee.

The hangover radiated from the back of my neck. I was exhausted, but too nauseous to sleep. The idea of getting ready for skiing seemed impossible. My mouth was parched. I went to the kitchen for water.

“Look who’s alive!”

I felt a hot sting of embarrassment. I matted down my hair. “What the hell happened last night?” I asked. “I haven’t been that drunk since college.”

“You. Were. A mess. Like, you couldn’t even stand.” Caroline was smiling, at least, as she told me this. She was laughing.

“Oh no. Was I really that bad?”

“We all were. Lizzie passed out on the bar. Courtney called someone a peasant. We met these two cousins and they started making out with each other. It was fucking weird.”

I remembered none of this.

“I don’t know if I can go skiing today,” I said.

“You’re going fucking skiing.”

“My head is pounding.”

“Take a Tylenol.”

I forced down some eggs and drank two cups of coffee. A thermometer suctioned to the window read twelve degrees. As I slipped my snow pa

nts on, I heard my grandfather’s voice in my head: If you want to dance, you gotta pay the fiddler.

We drove to the mountain in two cars—Caroline’s and Billy’s. I was in Caroline’s car. A fresh layer of snow dusted the trees. With every turn I fought the urge to vomit. My friends didn’t seem to have this problem.

Why did I get wrecked like that? I drank to have fun, to slow my anxious thoughts, to amplify my humor. But mostly I drank to connect. I wanted to feel a part of something. I wanted to be loved. I longed for someone to know me in all the ways I couldn’t know myself. But the drinking didn’t always get me there. It often netted out at oblivion. As we peeled up to the mountain, I wondered if I was the only one in the world who felt like this.

I lasted four runs. I was too sick. I leaned over my poles—heart pulsing, legs sore, a headache crenellating the grooves of my skull. I begged Caroline to let me take her Jeep back. I needed to lie on the couch, watch reality shows, and recuperate. I could meet them later for après.

I carried my skis through the resort, avoiding eye contact with the throngs of families whose bundled wholesomeness amplified my hangover. At the car I sloughed off my coat. I hadn’t brought shoes. I removed my ski boots and began to drive in my socks.

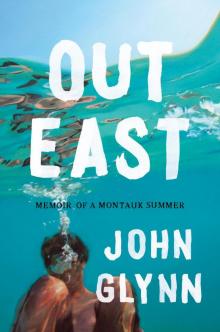

Out East

Out East